–

You found him the same way as everyone else: a six-second clip, filmed vertically, already at forty million views by the time it crossed your feed.

In it, a man stands in the driveway of a modest split-level home in Dayton, Ohio.

He holds a casserole dish.

Behind him, the front half of a delivery truck is buried in his living room.

Somewhere inside the house, a smoke detector is screaming, and on the lawn there is a shape under a blanket.

In some videos the blanket is blurred, but in most it is not.

The man is holding the casserole dish because he’d been coming home from a potluck at his church.

The shape under the blanket is his youngest daughter, Lucy, age seven, who’d been playing in the yard.

The truck driver had a cardiac event.

He’s dead too.

Job’s wife, Claire, and his two other children were in the kitchen.

They survived, but his son, Caleb, will never walk without assistance again.

The clip is six seconds long, and in it Job does not scream or fall to his knees. He stands perfectly still. The casserole dish does not even tremble in his hands. A neighbor off-screen says “Oh God, oh God, oh God,” and Job just stands there, and something about his stillness, the way his face holds its shape, is what makes it go viral.

You know you watched it.

–

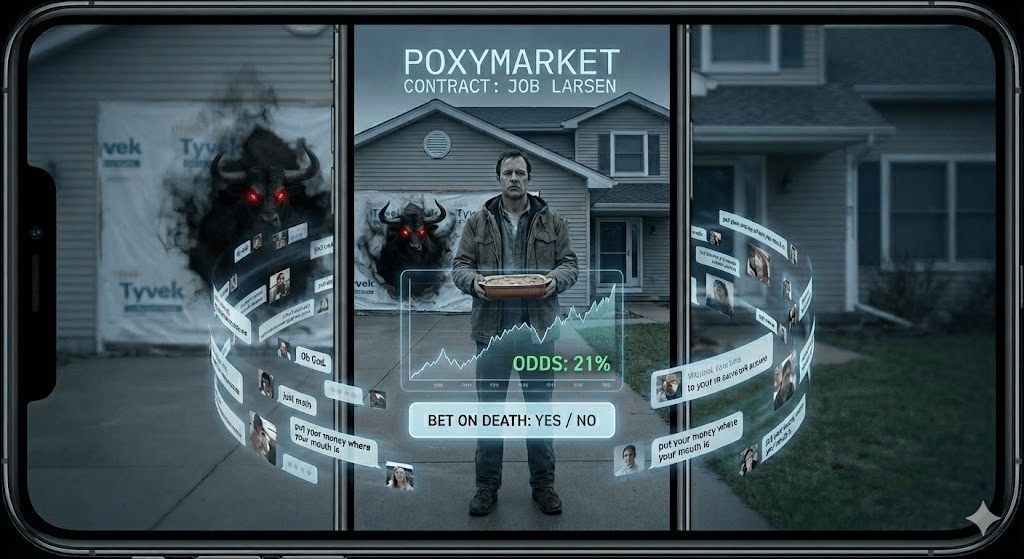

Within forty-eight hours, someone on Poxymarket, the prediction market where we all bet on everything from papal elections to whether a specific celebrity would cry on camera at the Oscars, created a contract:

**WILL JOB LARSEN OF DAYTON, OH COMMIT SUICIDE BEFORE DEC 31?**

Could have been anyone.

Could have been me.

Could have been you.

What matters is the opening odds were 12% and the end of day one volume was $1.4 million.

The comments were normal.

Some called it disgusting, some said they were the disgusting ones, some people threatened other people, some people called those people Nazis, and everyone placed their bets.

The comment with the most upvotes, from power user ColdLogic69, said, “The market just aggregates probabilities. If you think 12% is wrong, put your money where your mouth is.”

You put in fifty dollars on YES because why wouldn’t you?

I put more, because why wouldn’t I?

We’re tired of everyone making money but us.

If we ever feel guilty, we can always donate the winnings to a mental health charity.

The odds ticked up to 15%.

–

Job had worked for nineteen years as a claims adjuster at Inflationwide Insurance. He was, by all accounts, excellent at his job: patient, thorough, dedicated, and dependable. He stayed late, rarely took vacations, and didn’t cause drama in his department.

Three weeks after the accident, Terri, his manager, called him into her office.

“We love you, Job. Everyone here loves you,” Terri said, “but loyal clients, the ones we count on, are recognizing your name from your life event. It’s making some of them think about their insurance company. Some have even begun to accrue search histories asking for quotes from other companies. So, yeah. And you understand I’m just the messenger here, right Job? We all love you. Everyone here loves you.”

“Terri, what are you saying?” Job asked.

Terri looked at her hands. “It’s just optics, Job. You of all people know how tough optics can be.”

Job agreed optics could be very tough and understood why he had to leave for the good of Inflationwide.

He was grateful to receive a severance package.

After watching Job react to losing his job, Terri bet four hundred dollars on YES.

A few nights later when she was deep into her third glass of her 2020 Louis Jadot Domaine Duc de Magenta Morgeot Clos de la Chapelle Monopole, she concluded she had not once thought about the betting market before deciding to fire Job.

She then checked Poxymarket and saw the odds had moved to 22%.

–

You checked the app again.

I know it.

You can’t keep your mind off it, can you?

Neither can I.

It’s got its teeth on our cortex and we don’t have the time, the will, the skill, or the tools to make it let go.

So we check our weather app to pretend our interaction with our mobile information delivery device is practical and responsible.

Then we check our stock-trading app like someone who thinks they’re an adult.

LMT +15.15 (2.38%), RTX +1.08 (0.54%), NOC +7.51 (1.08%), GEO +0.74 (5.49%), and CXW +1.06 (5.94%) were all up, of course, but EDU −1.54 (2.56%), GHC −18.13 (1.69%), BFAM −14.93 (18.25%), HCA -5.07 (0.95%), THC −1.16 (0.50%), and UHS -0.76 (0.32%) were all down.

The red numbers make us feel sad.

–

The next month, June, Job got a call from his bank about the home-equity line of credit he’d taken out three years prior to renovate his kitchen.

After the accident, after the truck was removed and the living room was a cavity covered in Tyvek [DD +4.20 (1.23%)], the bank’s automated systems had flagged his account with the tags public tragedy, job loss, and elevated risk profile.

A letter arrived informing him that his credit line was frozen pending review.

He called the number the letter said he could call if he had questions or concerns.

He sat patiently on hold for two hours and sixteen minutes.

When someone Job believed to be human answered, she told him her name was Barb and that she was very, very, very sorry. Decisions like this were made by the bank’s model, and there was nothing she could do to change it.

A man named Dennis, who lived alone in a condominium near the bank’s windowless data center in Charlotte, NC, and monitored the conversations of the automated agents, recognized Job’s name from the video, listened to Job accept Barb’s statement as final without arguing, and put over $9,000 more on YES at 22%.

When Dennis checked the Poxymarket app while sitting alone in his condominium after watching a sports match he’d lost a bet on, he was relieved to see that the odds on Job committing suicide by December 31 had moved to 28%.

–

Claire tried very hard.

It’s important you know that.

She tried with a ferocity that should be called heroic.

She managed the CoFundWe, and raised sixty thousand dollars.

She drove Caleb to physical therapy three times a week.

She held Job at night when he lay rigid as a plank and stared at the ceiling with eyes that looked like they’d been emptied out with a spoon.

But Claire was also, and this is the important part those of us who condemn others seem to forget, a human being.

She was a human being.

And she was tired.

So one night, scrolling through her phone while Job lay silent beside her, she checked Poxymarket.

She saw the odds.

She saw what people were saying.

She did not place a bet, because she’s a human being.

But she did break.

–

To fix the Plytanium® (Koch Industries, private) covered hole in his home, Job filed an insurance claim with his former employer, Inflationwide.

His claim was denied.

The policy had a “commercial vehicle incidents on residential property” clause.

He appealed.

The appeal was denied.

He tried to hire a lawyer, but he could not afford their retainers with a frozen line of credit.

Simultaneously, the city cited him for the damaged facade of his home.

They gave him forty-five days to bring the property into compliance before they’d start fining him daily.

Job went to the city council meeting.

He sat in a plastic chair under fluorescent lights for two hours, waiting for the turn he’d signed up for days earlier, then explained his situation to a row of people who already knew his situation because everyone knew his situation.

Councilwoman Liz Hadley sat on the zoning board. In a moment of what she’d described to her husband as ‘morbid curiosity,’ she’d purchased a YES position at 30%. She listened sympathetically and then voted with the rest of the council to uphold the citation.

“We can’t make exceptions,” she said, “or the whole system falls apart.”

She said this with great conviction.

She believed it.

Anyone who heard her would have believed her.

The odds ticked up to 34%.

–

You googled “Job Larsen update” and read a profile in the Dayton Daily News (Cox Enterprises Inc., Private) in which Job was described by the automated writer as “stoic” and “a man of deep faith.”

The article mentioned that he still attended church every Sunday.

The comments under the article were predictably unpleasant and you did not read many.

You checked the odds.

They were at 36%.

Your fifty-dollar bet was now worth about eighty.

Mine was worth more.

–

The police visited Job on Tuesday, September 11th.

Someone had anonymously called in a wellness check.

Two officers arrived and asked Job if he was thinking about hurting himself.

Job said no.

The officers asked if he had firearms in the home.

Job replied he had a hunting rifle, which he had a license for, practiced with every Thursday at the Midwest Shooting Center in Beavercreek, and had been bequeathed to him by his father, Zerah, descendant of Esau, through his father’s will.

The officers of the law told Job, in a kind, apologetic manner, that they’d need to take his father’s hunting rifle, temporarily, for Job’s safety.

Job asked under what authority they were violating his constitutional rights.

The police informed Job this was only a precautionary measure and he’d receive his property back after Job had been formally evaluated by a psychological team.

Job again brought up the constitution of the nation in which he was a taxpaying citizen.

The officers asked for Job to wait one moment.

One of the officers stepped away, spoke into his radio, and walked to the curb, where, five silent minutes later, a police patrol vehicle pulled up flashing its lights and sirens.

Four police officers now stood across from Job.

One of the officers asked Job if he’d heard of Poxymarket.

Job said he had.

The officers looked at one another knowingly.

Another officer pulled out his phone and showed Job the screen.

The screen displayed “41%” in green numbers with three arrows next to them gyrating rhythmically, like the arrows were grinding on the numbers at a club where people still danced with one another.

Job said, “That’s strange, but I promise you I have no intention of killing myself.”

The officers looked at one another knowingly, again.

A third officer said, “Sir, we’re going to need you to step aside and inform us of the location of the deadly weapon.”

The officers moved forward towards the door of his home, and Job stepped out of their way so he wouldn’t accidentally run into them.

“Sir, where is the deadly weapon!” the fourth officer shouted in Job’s face as he walked into Job’s home. “This is your final warning!”

Job didn’t want to be rude to the government officials in his home, so he told them the truth.

The officials of his government took his rifle.

These police officers also filed a report that described Job as “agitated and potentially unstable,” which, as required by law, was reported to Montgomery County Children Services.

–

Remember the Poxymarket Super Bowl (NFL, Private Trade Association) commercial?

I agree with you.

It was one of the best Super Bowl commercials last year.

“We are not the avalanche, but we are the snow.” was a great way to end the visual tour de force.

But you already knew that.

The trustworthy voiceover in our head sure helped metaphorize our bet when we placed our tiny flake of snow on top of that mountain.

–

Claire found the police report the department had sent in the mail in October.

This was only two days after the Poxymarket odds on her husband killing himself on December 31 were up to 49%.

Before that, as she scrolled her phone next to her silent partner, she’d scanned Redhit threads and FouTube video essays titled “The Job Larsen Market: Late-Stage Capitalism or Just Math?” (1.2 million views) and “Why Job Larsen’s Family Will Leave Him and He Will Kill Himself” (2.6 million views).

Before that, she’d overheard a woman at church tell another there was a chat group where local people could share her husband’s daily movements, body language, the time the lights go on and off in their home, and other relevant data points.

Before that, when she’d broken, Claire had had a panic attack, dissociated from her body, and begun an anti-anxiety medication at the recommendation of her doctor.

She had not shared any of these events with Job.

Claire put down the police report, packed a few bags, put her children in the car, and drove to her mother’s house.

She left a note telling Job she needed space and not to worry, everything was fine. She told him it was temporary.

She did not tell him when her mother sat her down the next weekend and said, “Honey, I know this is terrible, but you have to think about yourself.”

The odds hit 55%.

–

The number is moving faster.

There are now six full green arrows slip slidin’ on the percentage that Job Larsen of Dayton, Ohio might kill himself on December 31.

Your bet is worth a hundred and forty dollars.

We’re part of something.

Something that ties us to millions of other people in the same beneficial position.

We got this one right.

When Job Larsen kills himself before December 31, it will prove us right.

We played an important role in this.

I hope we know which role that was.

–

On December 25, Job sat alone in his house.

The living room was still a wound.

The city fines were accruing.

The lawyer had dropped his case.

His bank account statement had little to say.

At the kitchen table Claire had wanted to renovate, Job thought about Lucy; how she’d trace a crack in the table with her finger and tell him she was following it to find treasure.

He thought about the people on the internet who were waiting for him to die.

He didn’t fully understand how the market worked, but he understood why it worked.

He understood why his family, his job, and his government had done the things they’d done.

He thought about the story of his namesake.

He’d read it many times.

He knew this type of thing happened sometimes.

He knew all he could do was try his best.

Job looked at the screen of his mobile information device and used his thumb to download the Poxymarket app, and his eyes to read the terms of service.

He found the contract, currently 75% with twelve green arrows lewdly shaking their money makers up and down next door.

He created an account, verified his identity, linked his bank account, and bet everything he had left on NO.

–

A post appeared on Redhit within the hour: *”JOB LARSEN JUST BET ON HIMSELF TO LIVE.”*

The comment sections fractured in the way they always do.

The odds dropped.

75% to 58% on Boxing Day.

By New Year’s Eve, the odds rested at 10%.

The market’s faith that Job Larsen would kill himself had evaporated.

–

Job called Claire after the New Year.

She answered on the fourth ring.

“Would you like to come home?” he said.

“Our home is broken, Job. It is not a place fit for children, especially Caleb.”

“I know.”

Silence.

Then Claire asked, “How much did you bet?”

“All of it.”

Claire laughed.

She knew it was inappropriate to laugh, but it went on for a long time.

When it stopped she was crying, and when the crying stopped she asked, ”Do we have enough to fix the house?”

“It’s already under construction. They’ll finish that and the kitchen renovation in less than three weeks,” Job answered.

“I think we’ll be free to visit around then,” Claire offered.

“I’m looking forward to it,” Job replied.

–

Dennis in Charlotte held strong.

He’d put thirty thousand dollars on YES at 12% one night when he’d gotten drunk after losing enough to hurt him in a bet on a boxing match. He meant to type $3,000, but he accidentally typed one too many zeroes. Now here we are.

But the bet seemed like a good one the more research he conducted. He added over nine thousand at 22%, doubled down at 34%, and borrowed against his Infiniti G35 [NSANY +0.31 (5.66%)]. The fundamentals were sound. The model was clear. This was just math.

On January 1, when the odds hit 10%, Dennis had lost more money than he’d made in six years at the bank, and owed more than he’d make in the next three.

He sat in his condominium and refreshed the page and felt something curdling inside him that no one had ever thought to teach him how to name.

A commenter named MarketMakerMike posted a final analysis titled “Post-Mortem on the Larsen Contract” in which he argued that the market had been “distorted” and that “the rational case for YES had been strong.”

Fourteen people liked it.

Dennis was one of them.

–

So your fifty dollars was gone.

So my money was gone.

It wasn’t a lot.

Do you remember when you closed the app and moved on?

Job tried to move on, too.

But Dennis didn’t move on.

–

On January 3, a new contract appeared on Poxymarket.

It was posted at 2:47 a.m. by an account created that same night, with a username that was just a string of numbers.

The contract read:

**WILL JOB LARSEN DIE BEFORE MARCH 31?**

Opening odds: 4%.

The moderators flagged it within minutes.

A debate erupted in comment sections all over the internet about whether it violated the platform’s terms of service.

A Poxymarket spokesperson issued a statement saying the contract was “under review.”

Another contract went up in Helshi, a rival prediction market with a higher valuation.

This contract opened with 6% odds and a volume of 3.4 million.

Though odds were longer, the market’s appetite for Job Larsen’s life was clearly not sated.

So Poxymarket released the contract from review, and allowed betting to resume.

The odds went up to 7% with a single green arrow dry humping the number.

There weren’t many comments this time.

And not every major media outlet picked up the story.

And those that did put it behind paywalls.

We didn’t bet on this one.

We looked at it, but we didn’t place a bet.

The odds were too low.

–

It was Claire who showed Job the contract when it reached 20% in February.

He read the contract twice, then put the phone down on their new kitchen table.

“We should call the police,” Claire said.

“And tell them what?” said Job.

Claire didn’t answer.

She picked up the phone and looked at the number again.

20%.

And more than one green arrow wiggled their bits suggestively.

–

By March 20, Dennis, in his condominium in Charlotte, checked the status of the contract every few minutes.

Dennis knew Job Larsen’s address.

Everyone did.

It had been in the Dayton Daily News (Cox Enterprises Inc., Private) profile.

It had been on the CoFundWe page.

It had been in the police report, which someone had obtained through a public records request and posted to a Miscord server with four thousand members.

Job Larsen lived at 414 Greenleaf Drive, Dayton, Ohio, 45417.

His front door had a lock that a real estate listing from 2011, still cached on Zillow, described as “original hardware.”

Dennis had known all this for months.

The odds on the new contract hit 21%.

–

In the original story of Job, God speaks from the whirlwind. He restores what was taken. He doubles Job’s wealth. He gives him new children, as though children are replaceable.

But this is not that story.

God does not speak from the whirlwind because there is no whirlwind.

You know this, and I know this.

There are only servers slurping up water and electricity somewhere and numbers that tick upwards or downwards as millions of people’s body chemistries react accordingly.

On March 30, Job Larsen stood in his driveway.

It was a pleasant March day, and Job was looking forward to the warmth spring brought to the Miami Valley.

Claire was inside putting Caleb to bed.

The street was quiet.

A car he didn’t recognize was parked at the end of the block.

It had been there for an hour.

Its engine was running.

Job looked at the car.

The car didn’t move.

Job stood there for a long time, thinking about that car before he went inside and locked the original hardware lock and sat at his kitchen table and didn’t sleep.

The car was gone by morning.

The odds remained at 21%.

–

You’re still here, reading?

I’m still here, writing.

You want to know what happens?

You want to know whether the man in the car was Dennis or a stranger or nobody?

You want to know whether Job lives or dies?

Why does it matter?

The market is open.